Filipinx-Americans and the United Farm Workers Movement: Invisible in the Eyes of U.S. History

- bryannaempowertoch

- Oct 1, 2020

- 4 min read

**As October is Filipinx-American History Month, this piece is dedicated to the manongs (the Filipinx-American labor movement organizers) and the Filipinx-American field workers who have historically fought for social justice and workers’ rights.

Growing up, I was told stories about my grandfather and his experiences working as a farm worker along the West Coast - about the physically demanding labor, the long work days, the poor treatment of field workers, the discrimination towards Filipinxs in California, and the friendships he made with his fellow field workers in Delano. For most of my life, I believed that this experience was unique to my grandfather; I had no idea that his story was just one example of a broader narrative in Filipinx-American history.

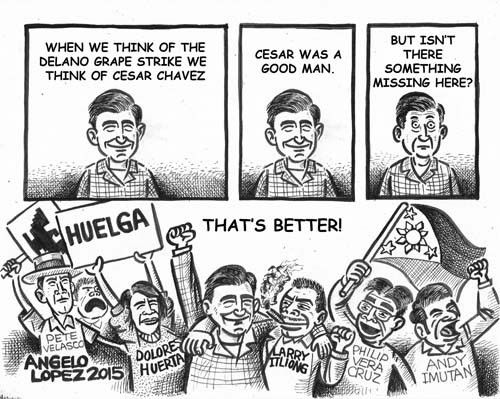

The United Farm Workers Movement (UFW) and César Chávez are highly recognizable names, particularly in California. One of the leaders of the movement, Dolores Huerta, was an integral figure in the farm labor movement and continues to advocate for equality and civil rights for the working poor, women, and children to this day. Many schools in California are encouraged to include curriculum surrounding the history of the UFW and the role of César Chávez. I, myself, had learned about the significance of Chávez and Huerta through my history curriculum from elementary through high school - but not once did I encounter an acknowledgement of the role of Filipinx migrant farm workers in the farm labor movement.

It was not until I began actively researching outside of my educational settings that I learned about the history of Filipinx-American farm workers. I discovered that through the 1920s and 1930s, an influx of Filipinx immigrants arrived in the U.S. to work on fields along California and the Pacific Northwest. As a result of the discrimination they experienced, Filipinx-American farm workers began organizing under the leadership of manongs (Ilokano word of respect, meaning “older brother”) Philip Vera Cruz, Larry Itliong, Pete Velasco, and Andy Imutan. In the 1960s, the Filipino Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) was officially established.

It was the efforts of AWOC that spurred the Delano Grape Strike in 1965. After eight days of striking, AWOC was joined by Chávez, Huerta, and the National Farm Workers Association. The merging of these groups led to the formation of the UFW, the union that many of us are familiar with today. The critical point to understand here is that the UFW Movement was not solely a Xicanx effort, but a collective effort among Xicanx and Filipinx farm workers.

Chávez and Huerta deserve all the respect placed in their historic and revolutionary work, but the pivotal role of Filipinxs in the farm labor movement must be recognized as well.

So why are Filipinx Americans often left out of this history? If I did not take it upon myself to research the history of Filipinx-American farm workers, I may have never known. The truth is, Filipinx-American history, like many cultural minority histories, is not accessible in U.S. curriculum.

Filipinx Americans are often referred to as “The Forgotten Asian Americans”, a phrase coined by Filipino historian, Fred Cordova. One possible reason for this could be attributed to the model minority myth that serves to invalidate the experiences of Asian American groups and render the diverse experiences of certain Asian American subgroups, such as Filipinxs, as invisible. Another possible explanation could involve the history of U.S. colonization in the Philippines. During the U.S. colonial period in the Philippines, American educators were sent to the islands to indoctrinate Filipinxs with notions of U.S. civilization and superiority. In this way, U.S. histories are reinforced while Filipinx realities are suppressed.

In an article by Psychology Today, one of my academic idols, E.J.R. David, illustrates the neglected histories of Filipinx-Americans:

“You see, Filipino banishment goes back to the fact that there was a Philippine-American War that lasted for 15 years and during which thousands—some say 1.4 million—Filipinos were killed by Americans, but yet such a war seems to be unacknowledged, hidden, and forgotten. Filipino marginalization goes back to the days of the manong generation, whose struggles in the farms of Hawaii, California, and Washington—as well as in the canneries of Alaska—continue to be unknown to many. It goes back to how the hard work and leadership of Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, and other Filipino farmworkers are overshadowed by the celebrity of Cesar Chavez. It goes back to how President Franklin Roosevelt pledged that Filipinos who fight for the United States during World War II would be granted citizenship and military benefits—so over 250,000 Filipinos heeded the call—but shortly after the war ended that promise was taken back with the Recission Act of 1946. It goes back to the many ways in which Filipino people have contributed to this country’s rise as a global power, but the American masses remain oblivious to such historical and contemporary reality.”

The U.S. education system must make efforts to include Filipinx-American history in their curriculum. In particular, California, New York, Hawai’i, Illinois, Nevada, and Washington - states with some of the largest Filipinx populations in the nation - should provide more representation on an ethnic group that has meaningfully shaped the nature of U.S. history.

Today, California field workers are enduring conditions that seem more severe than ever. Workers are fighting through the demanding labor, the extreme heat, the thick smoke, and the risks of COVID-19 to harvest food for our nation - all while being paid less than a liveable and humane wage.

Though the number of Filipinx-American farm workers have decreased since the 1900s, we must continue to advocate for field workers’ rights. We must not forget that many of our roots come from farm workers. We must celebrate the strides of the manongs and workers who built a major historical movement. We must continue to pass down our vibrant histories, so that future generations may understand what social justice means in our community.

.png)

Comments